Today a friend in the justice movement texted me these words: “Happy New Year. I’m depressed.” In trying to offer some advice, I summarized the remarks quoted below, which had made me feel better about life.

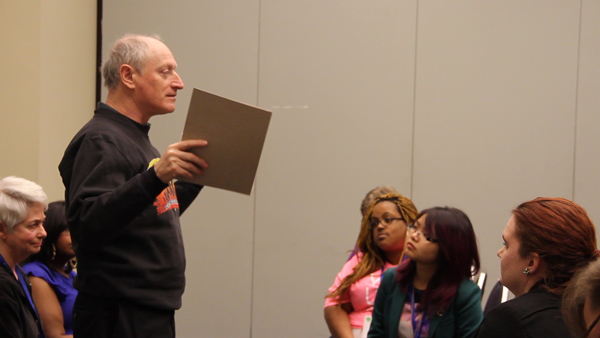

The author and speaker, Paul Booth, was a leader in the 1960s at the beginning of the student movement, directing the first march on Washington against the Vietnam War, and organizing the first sit-in at the Chase Manhattan Bank exposing it as a “partner in Apartheid.” He and his wife Heather Booth spoke at a well-attended panel discussion called “Sustaining a Lifetime of Movement” at Rootscamp 2014.

This is what Paul told a room full of progressive activists, all dedicating their lives to causes and wondering how to keep themselves sane in the process:

As I reflect on my lifetime in the movement, I think about the campaigns, organizations, mentors, the wins and defeats, the social changes (those to which I contributed and those I saw), and, particularly, the people: colleagues, and especially this remarkable woman Heather Tobis Booth, my life partner and political partner.

I have come to the conclusion that it is the most intense of the political relationships that have the largest impact on today’s question: how to sustain a lifetime of movement.

I was 18 when I joined the newly launched Students for a Democratic Society. SDS started small, there were just 50 of us at Port Huron where we wrote the manifesto of the New Left in 1962.

Here’s what we did together:

• We formulated and articulated a shared vision for social change

• We built a large membership organization

• We launched the movement against the Vietnam War, a mass movement that rocked the country and ultimately won its fight

• We organized together, for civil rights, university reform, against nuclear weapons. We organized together, learned together and took risks together.

Five intense years. The organization we created only lasted briefly. It made a big difference, it was huge, but turbulent.

It wasn’t sustained, but I was. Not all of those 50 founders or the hundreds, then thousands, who joined us, sustained a life in the movement, but many did, in many arenas.

I place intensity of mutual commitment at the top as I sift through factors that contribute to sustainability of activism. Then there is winning, getting decent salary compensation, and making room for the non-movement parts of life. All of those contribute, but less.

You can find examples of cohorts of mutual commitment throughout movement history. In civil rights history, in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. In feminist history, community organizing, union organizing, electoral campaigns, and in student movements.

Look at your own situations. Ask who you’re working with, side by side. Are you formulating and stretching your ambitions together? Are you finding friends, with whom you can foresee sticking with, working with and staying connected to?

Are you learning from each other?

And are these the people who have your back? And for whom you would stop what you’re doing, to lend your support?

Movements can’t be sustained without well-built organizations. (That’s a subject for another workshop.) But the best organizations can’t produce high-ambition cohorts. They can be a framework. But cohorts like that are created, intentionally or unconsciously, by you and your motivations. Your moral values, your political ideology, your ambitions, are the necessary ingredients.

And when they are shared, knitted together with people you throw in with and throw down with, you can make history, make change, and make a life of which you can be really proud.

My camera was in my backpack when Paul spoke the words above, but I brought it out soon afterward. Stay tuned for video I shot during this panel discussion.

Please support Story of America with a tax deductible donation.