Sometimes we forget that old people were not always old people. We see them as living on the other side of a wall, rather than of as part of continuum of which we are all participants at different stages.

Sometimes we forget that old people were not always old people. We see them as living on the other side of a wall, rather than of as part of continuum of which we are all participants at different stages.

When I first met Wendy’s father-in-law at Thanksgiving 1994, he seemed like an old person to me, and, because he doesn’t speak very much English and I don’t speak any Japanese, I didn’t think much more about of him for the next 18 years. Wendy, my mother’s cousin, is a Chinese American woman married a Japanese American man named Ken Hayakawa. This past Thanksgiving, after dinner, we were putting Harry Potter on for the kids when Wendy handed me a new book: Nisei Soldiers Break Their Silence by Linda Tamura. It was opened to chapter 8. “Read this, it’s about Ji-Chan (grandpa),” she said.

Kenjiro Hayakawa was born in Hood River, Oregon in 1919, then educated in Japan. At the end of his studies, he returned to America to avoid being drafted into the Japanese Imperial Army which was invading and occupying neighboring countries in Asia. He was then drafted by the United States Army and reported for duty in November 1941. Better to fight for America than for Japan, he had thought.

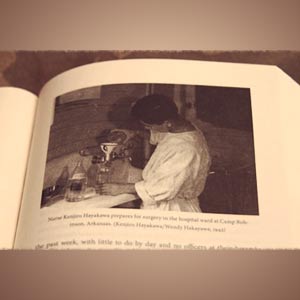

By the time I got to the page 113, which featured a photograph of Ji-Chan at Camp Robinson, Arkansas in 1942, I was sitting at the dinner table almost next to him. I looked at him and pointed to the picture. His unassuming but effulgent smile, which I returned, was the most significant communication we had ever had up to that point. I went on reading.

By the time I got to the page 113, which featured a photograph of Ji-Chan at Camp Robinson, Arkansas in 1942, I was sitting at the dinner table almost next to him. I looked at him and pointed to the picture. His unassuming but effulgent smile, which I returned, was the most significant communication we had ever had up to that point. I went on reading.

Next to Kenjiro sat Yoshiko, known to me as Ba-Chan and as Grandma Hayakawa. Yoshiko is fluent in English so I’ve gotten to know her quite well over the years. Along with 120 thousand other American citizens, she was ripped from her home as a result of Executive Order 9066, issued by President Franklin Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. She was 13. Yoshiko and her family were held captive at Santa Anita Park, a thoroughbred racetrack near Los Angeles, where 17,000 people were held, many of them in horse stables. “We were not in horse stable, but near them” and “There was a street named Seabiscuit,” she told me quietly. Yoshiko and her family where then loaded on to trains and shipped to Rohwer War Relocation Center in Desha County, Arkansas. “They were very old rail cars that had not been in service for a long time,” she told me. “And, they didn’t bother to dust them off.”

As it happened, Rohwer was near Camp Robinson, where Kenjiro was stationed. On their days off, the Japanese American soldiers would cram themselves into motor cars to go and visit the internment camp. They wanted to be with other Japanese Americans, “and mostly to eat Japanese food.” Yoshiko added. It was during these visits that Grandma and Grandpa Hayakawa fell in love.

But I didn’t just learn about the camps. I also learned about how our soldiers were treated in the WWII era. I’m speaking of Japanese American soldiers, but let me make this plain: they were OUR soldiers. And, whatever reverence and whatever regard we afford to members of our military today, we should afford the same to all members of our military. They are ALL our soldiers.

While their families were in prison on account of their heritage, Japanese American soldiers were subjected to a pattern of demeaning and disrespectful treatment crystallized in Nisei Soldiers Break Their Silence by an April 1943 incident at Ft. Riley in Kansas. During a visit by President Roosevelt, 120 soldiers of Japanese heritage were marched into an aircraft hanger and held at gunpoint for nearly four hours until the president had departed. Many of these same soldiers were then involved in March 1944 incident at Ft. McClellan, also in Arkansas, where about 100 men congregated outside battalion headquarters to protest their treatment.

Kenjiro was among them, and he was also among the 21 who persisted in their struggle even though the threatened response was court martial. I won’t go into detail about Kenjiro’s court martial, a compelling story of civic and personal courage, followed by imprisonment (during which, Yoshiko said, she wrote him letters from the internment camp). Forty years later, 11 of these heroes, including Kenjiro, had their dishonorable discharges reversed (the other 10 had declined to participate in the appeal process).

Learning of all this, I was reminded of Capt. Bruce Yamashita who fought for equality in the 1980’s and 90’s, and Lt. Dan Choi in recent years. I was reminded of my grandfather’s brother, Tommy Amer, who, after serving in WWII, was instrumental in ending segregation in California when he and an another Asian American veteran challenged a neighborhood covenant banning the sale of homes to non-whites, leading to a landmark decision in the California Supreme Court. And, of course I was reminded of the fact that Kenjiro’s son, Ken, fought in the first Gulf War and his grandson, Colin, fought in Iraq and Afghanistan, continuing the family’s tradition of service to our country.

As my sister snapped the photos you see here, it occurred to me that this family, like many Japanese American families today, would not have to come to be if not for an historic injustice. And, I thought about how I might never have known about Kenjiro’s heroism if not for a book providing me the opportunity to ask about it.

As my sister snapped the photos you see here, it occurred to me that this family, like many Japanese American families today, would not have to come to be if not for an historic injustice. And, I thought about how I might never have known about Kenjiro’s heroism if not for a book providing me the opportunity to ask about it.

Political strategists in recent weeks have marveled at the fact that minority communities tend to shun candidates and political parties that seek to rob minorities of equal protection under the law. Perhaps they assume we don’t know our history. And, perhaps we don’t know it as well as we should. But the experts overlook an important truth that really sunk in for me this Thanksgiving day: Our families are products of American history, and, whether or not we know all the details, we know intuitively that continuing the fight against institutionalized racism is our duty to our parents and our grandparents.

We will be more effective in modern day struggles if we better understand the triumphs, defeats, compromises, and ever-present echoes of days gone by. These lessons are waiting to be learned from members of our family and our community — if we remember to ask them in time.

Please support Story of America with a tax deductible donation.