Editor’s Note: This is an update to a powerful essay published on April 24, 2014 on storyofamerica.org, Not a Monster’s Daughter. It included this breathtaking line: “My name is Megan A. Collins, I am rape conceived and I should be afforded the right to my own history. This is my story.” The update is in two sections: “Black Boxes” and ““Reflecting on the experience of publishing my story.”

Black Boxes

Though most adoptees could not imagine a time when record access would be open, on March 20, 2015, the state of Ohio opened all sealed adoptions finalized between 1964-1996. The option was given to birth parents to have their name redacted from the original birth certificate if they filed the correct forms by the March 19th deadline. A basic medical information packet was required to be completed for this to be an option. Of 400,000 records, one hundred and fourteen redactions were said to have been completed by the deadline.

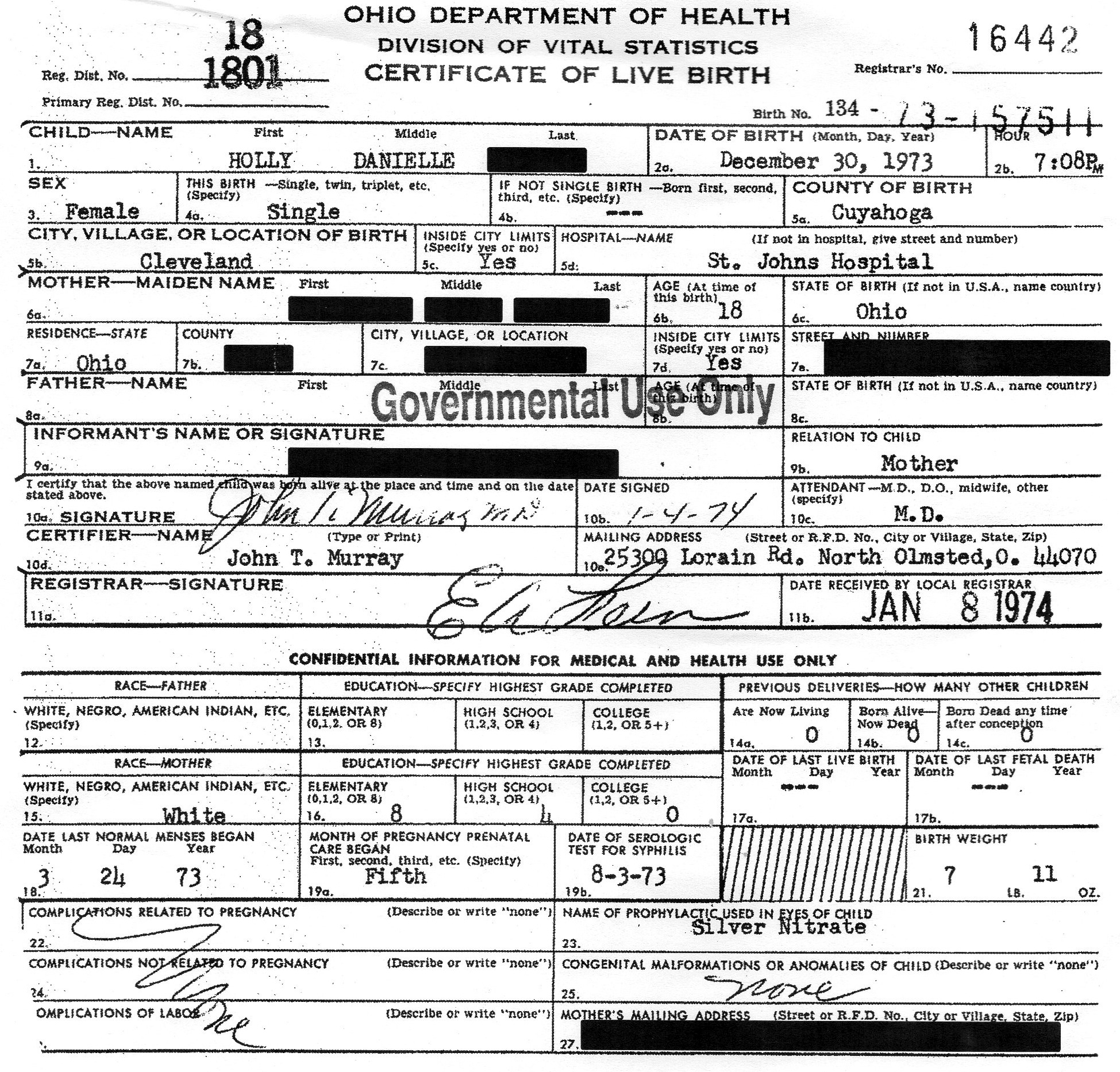

I had located my natural mother in 2011 after posting my birth information on an adoption website. A research assistant helped me to identify my birth name, Holly D Trexler, and locate my birth family.

I contacted my birth mother in 2012 and despite my hopes, she denied giving birth to me. We spoke for roughly four minutes while I explained to her my urgent need for medical information. I knew when she didn’t hang up right away, that I had found the right person. She ended the call by saying “I hope you find what you’re looking for.” Her voice broke only once, when I thanked her for taking the call. I said that I had waited my entire life to hear her voice. It was true, I had.

There are times I try and remember her voice but all I remember is her husband repeating “what do you want?” and telling her it was me. I heard her tell him she didn’t want to talk to me and he said “you need to.” The hardest moment in this journey so far was accepting the fact that I was her secret, and I was expected to stay a secret.

After speaking with my birth mother and getting no information, I was left no choice but to keep researching my history. I found a great deal of information about my family through death records, obituaries and military information. It’s horrible to feel like you are a voyeur of your own history; to know that I’m not supposed to know anything about it.

For the next four years, I wondered what the “D” in my middle name stood for. I had assumed it was Dianne as this is the name of my birth mother’s sister. I also wanted official confirmation of the name Holly D. Trexler on my original birth certificate.

When I opened my original birth certificate, seeing the name “Holly” was validating. I had spent years of my life wondering if that really was my birth name and now had tangible proof. When I saw “Danielle” as my middle name, I was surprised, but the sister I spoke of had a twin brother named Daniel, so I thought it could be a reference to this or maybe it was chosen randomly.

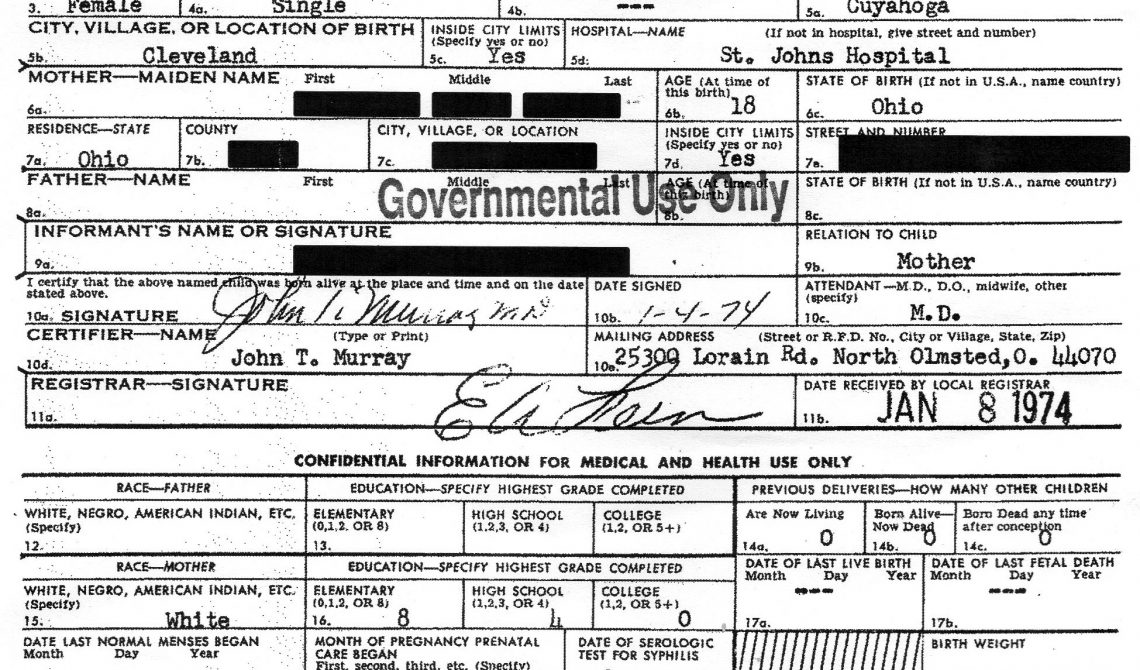

I then saw a black box where my last name should be. I expected some redaction in theory, but I wasn’t emotionally prepared to see black boxes all over my birth certificate including over my last name. It shocked me. Page after page of black boxes and missing medical information and a box checked to inform me she wanted no contact at this time. It also stated that the preference form could not be enforced.

Four years after the original call to my birth mother, I left a message on her voicemail. I heard her voice again for a moment and it was painful. I am sure I rambled through the message as I plead my case for more information. I think the voicemail disconnected at some point. I left my email and phone number. Predictably, no call or email has come in the last two weeks.

It’s absurd that I received an original birth certificate with my last name replaced with a black box, my birth mother’s name as a row of black boxes and the birth father information as blank spaces. This is not the original birth certificate. It is a legal document that was changed to reflect the legislation currently, just as my other birth documents are.

It has always seemed odd to me that more emphasis is put on protecting the birth parents’ identity rather than giving the adoptees the truth and information that could save their lives. I have a hard time believing this is morally defensible. Every part of me says I have a right to accurate information on my birth certificate. I shouldn’t have a black box over my last name.

Reflecting on the experience of publishing my story

Reflecting on the experience of publishing my story

When I first published my story last year, I was not sure how it would be received. Although I had a firm commitment to the dialog that would be started, I also knew I would be criticized publicly and I was.

In the weeks that followed, comments were left on different pages on facebook expressing that I “could be the antichrist,” and that I really was a “monster’s daughter.”

I got messages from strangers suggesting that my biological mother’s rapist would come find me and rape me or my daughters. There is no way to describe what it did to me. I also received threats. My daughters’ elementary school was put on notice.These events forced me to look closely at myself and my story.

People chose different parts to pull apart. I was spoken of as though I wasn’t watching the comments or emails as they came in. They would speak of how I had been so obsessed with my adoption that I ruined my marriage. There was a lot of stress from multiple surgeries, resentment, trying to keep our children in private schooling in a new state I had never planned on moving to, a strain of e-coli that caused me to lose fifty pounds in four months, oh and I maybe was a little too strong for his family to handle. Like I said, many reasons and yes, my search too. I was surprised by how much liberty people took with their assumptions.

Then people came forward with their own stories. Each of their stories offered valuable insight. By recognizing parts of themselves in my story, people were finding their own voices. It was powerful.

I also connected with dedicated and compassionate lawmakers and advocates who work diligently for access to birth records. It was empowering to know so many cared.

Someone has to speak of the things that make us uncomfortable. When I found out that I was rape conceived almost twenty years ago, I could not face the stigma associated with this. I felt I had nowhere to turn for support. No one wanted to talk about it. I was just supposed to suck it up and hide it.

It was brought to my attention that some believed that I was letting my birth father and yes, a rapist off the hook in “Not a Monster’s daughter.” This was not what I was referring to when I stated I was not a monster’s daughter. I am the daughter of the father who raised me. Being rape-conceived does not define who I am and I refuse to continue to place shame on myself for my birth father’s crime.

I also want to be clear that I do not place blame on my natural mother for not wanting to have a relationship with me. I am frustrated with a system that I believe failed me.

It is hard to know you are a reminder of the worst experience of someone’s life. It is frustrating that no one reported the crime despite knowing who the rapist was. It was a different time. Abortion was legal just weeks prior to my conception, but it was not available to everyone, many could not afford it and some could not live with the shame of it.

The decisions about our bodies should never be made out of shame or fear, or someone’s opinion of how our value is calculated. It isn’t easy to put your innermost self on display but there is a strength that comes from letting go.

I am not Holly, the monster’s daughter; I am Meg, a Collins’ daughter.

Please support Story of America with a tax deductible donation.